Do CBE Schools Benefit Students? Six Core Features May Make the Difference.

In traditional K-12 schools, students move through lessons, classes, and grades in lockstep with their same-age peers. Students who learn quickly must wait for their peers to catch up—while students who are struggling may be left to fail, repeat, or simply progress without ever fully mastering needed knowledge and skills.

Another approach sets the bar high for all students—but offers more personalized support and allows each student to move at his or her own pace. When students master a set of skills or knowledge, they move forward. When they struggle with a concept or skill, they get the extra time and help they need to succeed.

This high-bar, individualized support, flexible-pace approach is competency-based education (CBE). It’s spreading across the country and showing promise for promoting positive student outcomes. Forty-two states are planning, piloting, or implementing CBE initiatives according to a 2015 report by iNACOL, the International Association for K-12 Online Learning.

But even with so many states jumping on the CBE bandwagon, until recently, surprisingly little research had been conducted on the relationship between CBE and student outcomes.

AIR’s new Study of Competency-Based Education, funded by the Nellie Mae Education Foundation, examined CBE policies and practices for ninth graders in 18 high schools in three states, exploring how participation in CBE might influence students’ learning capacities. Ten schools self-identified as “competency-based education” schools. Another eight, in comparable settings and serving similar students, did not and so became our comparison schools.

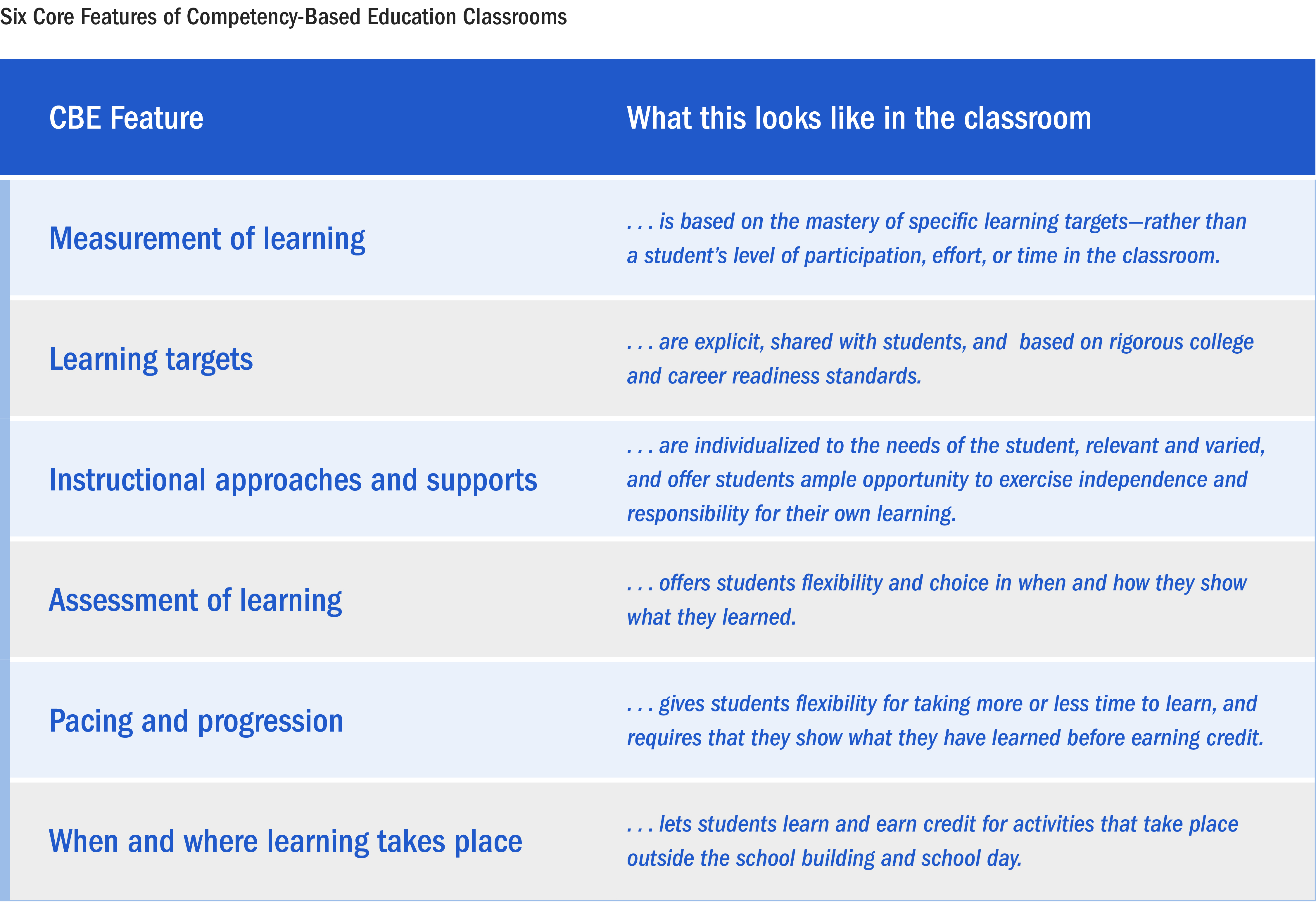

AIR’s study identified six core features of CBE-based classrooms. We surveyed administrators, teachers, and students to see whether these CBE features were being implemented in all 18 schools—both CBE and comparison.

Next, to see how students were potentially benefitting from CBE, ninth-graders completed surveys about their attitudes and beliefs, skills, and behaviors in areas associated with school success. Students were asked, for example, about their motivation to learn, their ability to manage and regulate how they learn course material, their study habits, and their classroom behaviors. Prior research has shown that these learning capacities are associated with students’ success in school.

Study Findings:

The study found several positive associations between students’ experiences of core CBE practices and positive changes in their learning capacities throughout the school year—regardless of whether students were in our CBE or comparison schools. For example:

- Students from both CBE and comparison schools who reported having clear learning targets and who believed they had to master those targets to earn credit showed growth in their intrinsic motivation and self-management skills.

- Students from both CBE and comparison schools who reported being given extra time to finish math coursework showed increased motivation, confidence, and regard for math.

- Students from both CBE and comparison schools who reported having the chance to retake exams to show mastery—even if they had previously failed—showed increased confidence in their mathematics ability, and they reported better study and self-management skills.

While exposure to CBE features appears to benefit students, our study also found that many “CBE” schools didn’t consistently and uniformly implement the core CBE features and that many “comparison” schools also reported using at least some of the core features.

What’s the lesson?

Simply calling a school “CBE” isn’t enough. States, districts, and schools that want to realize CBE’s potential must look beyond the CBE label to make sure they have a clear definition of which policies and practices constitute competency-based education—and ensure that these core CBE features are happening in every classroom every day.

Wendy Surr is an AIR senior researcher and the Lead for the Regional Deeper Learning Initiative.