Exploring Urban-Rural Disparities in Accessing Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder

While opioid overdose deaths have been rising in the U.S. for decades, there has been an unprecedented increase in such deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic. Preliminary data suggest opioid overdose deaths were roughly 38 percent higher in January 2021 than they were a year prior. Stress and anxiety resulting from job loss, isolation, and business closures during the pandemic are factors associated with substance use disorder and relapse from recovery. The acceleration affects individuals and communities and has resulted in higher health care costs, lost productivity, and increased demands on the health and human service sectors.

Understanding where overdose deaths are occurring and pinpointing the need for and ability to access opioid use treatment are key to addressing this issue. Rural and urban communities alike have experienced an overdose crisis, but there are some known differences in access to treatment and general health care. For instance, 56 percent of rural counties do not have a provider who can prescribe buprenorphine, a treatment for opioid use disorder. Further, 2 percent of Americans living in urban areas are without access to a buprenorphine provider, compared with 30 percent of rural residents. Residents of rural areas also face significant barriers to health care, including long distances to health care facilities, lack of public transportation, lower average incomes, low health literacy, lack of health insurance, stigma, and lack of broadband internet to take advantage of recent expansion of telehealth services.

Identifying Need for and Access to Opioid Use Disorder Treatment

AIR and IMPAQ experts analyzed data from a recent U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Inspector General (OIG) study to further understand differences between rural and urban areas. All analysis pertains to data from 2018. In our analysis, we used two county-level indicators defined by the OIG study:

- Counties with a high need for opioid use disorder treatment services. The OIG study classifies counties as being in high need for such treatment services if they ranked above the 60th percentile for three measures: age-adjusted drug overdose mortality rate, rate of retail opioid prescriptions dispensed, and the rate of nonmedical use of pain relievers.

- Counties with low-to-no patient capacity for prescribing buprenorphine. The patient capacity rate, defined by the OIG study, is the maximum proportion of county population that can be prescribed buprenorphine. If their patient capacity rate was at or below the 40th percentile of the distribution, counties were designated as having low-to-no capacity for opioid use disorder treatment.

Rural and Urban Differences

Based on our analysis, there are several significant differences between urban and rural counties in terms of need for and access to buprenorphine. Our analysis shows:

Overall, 35 percent of rural counties and 37 percent of urban counties have a high need for opioid use disorder treatment. However, 74 percent of rural counties and 48 percent of urban counties have low-to-no capacity for buprenorphine.

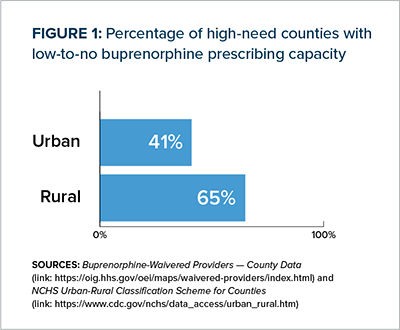

Among rural counties with high need, 65 percent have low-to-no capacity for buprenorphine prescribing, compared with 41 percent of urban counties with high need.

Our analysis also explores geographic disparities among rural and urban counties by census regions (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West).

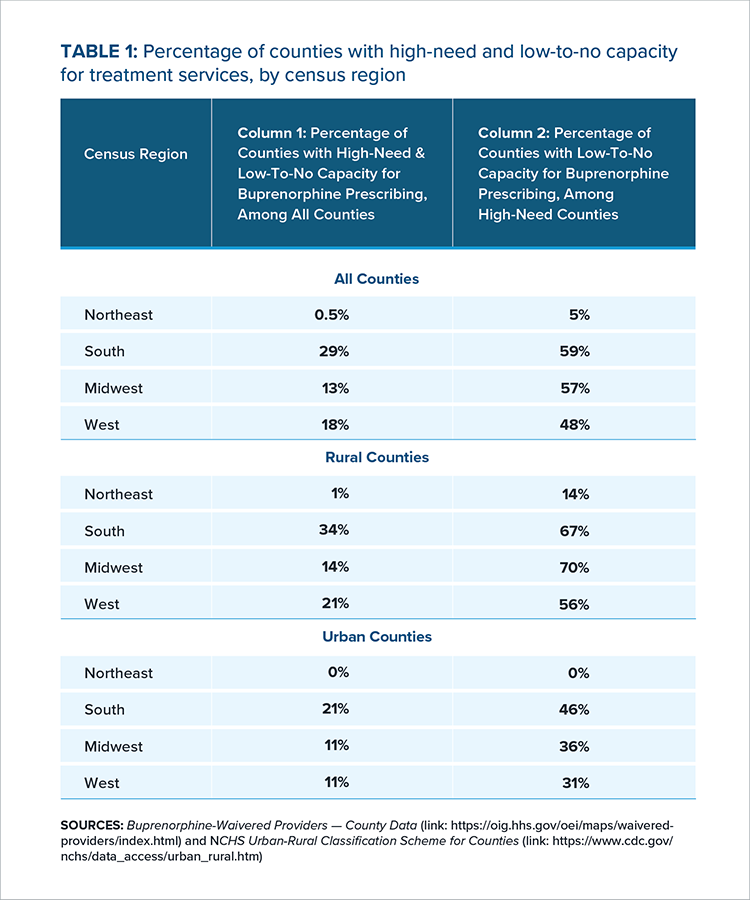

As shown in Table 1, Column 1, the South has the highest prevalence of counties that are high need and have low capacity for treatment services. The West and Midwest have 18 percent and 13 percent, respectively, of counties that are high need and have low capacity-to-no capacity. Only 0.5 percent of counties in the Northeast are high need and have low capacity-to-no capacity.

For all four census regions, prevalence of high need and low-to-no capacity is higher among rural counties. Thirty-four percent of rural counties in the South and 21 percent of rural counties in the West are high need and low-to-no capacity. In the Midwest, 14 percent of rural counties are high need and low-to-no capacity. Only 1 percent of rural counties in the Northeast are high need and low-to-no capacity.

Rural-urban disparities are most pronounced in the South and West, where rural areas have a higher prevalence of counties that are high need and low-to-no capacity by 13 and 10 percentage points, respectively.

Column 2 of Table 1 shows that in the South, Midwest, and West, the majority of high-need counties have low-to-no capacity for buprenorphine prescribing. While the prevalence of low-to-no capacity for buprenorphine prescribing among high-need areas is also high among urban areas, it is substantially lower than it is in rural counties.

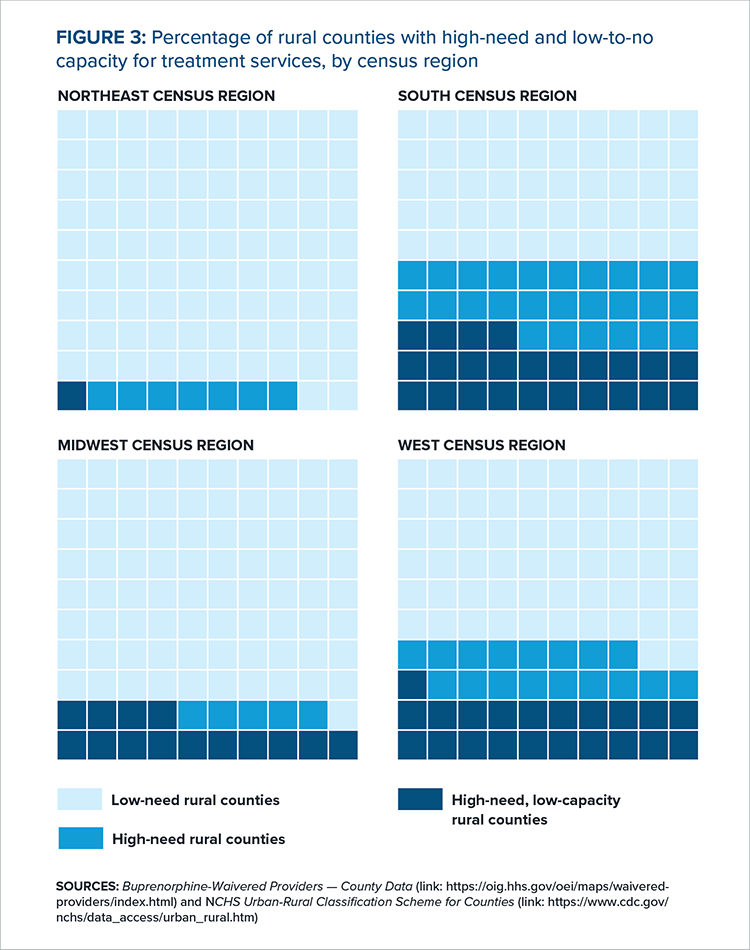

As is evident in Figures 2 and 3, the South and West Census regions have more rural counties that are both in high need for opioid use disorder treatment and have low capacity for buprenorphine prescribing, than the Midwest and Northeast.

FIGURE 2: MAP OF HIGH-NEED RURAL COUNTIES WITH LOW-TO-NO CAPACITY FOR BUPRENORPHINE PRESCRIBING

Why Rural Counties May Face Low Buprenorphine Prescribing Capacity

Our analysis shows that rural counties in high-need areas have a substantially lower capacity for prescribing buprenorphine than their urban counterparts. We also find that the South and West census regions have the highest proportion of counties that are both high need and have low treatment capacity.

Several factors may contribute to low buprenorphine prescribing capacity in rural counties, including that:

- Rural areas face shortages of health care professionals, including those within the behavioral health workforce. In fact, two-thirds of Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)-designated Mental Health Care Professional Shortage areas are in rural or partially rural parts of the country.

- Rural providers may encounter more barriers to prescribing buprenorphine, as shown in previous research. Rural providers may have concerns, such as low confidence in managing patients with opioid use disorder because providers themselves lack specialty care backup and patients do not have access to support services. Stigma, time constraints, and financial concerns also play a role in resistance to obtain a waiver from the government to prescribe buprenorphine. While all providers find it challenging to stay up to date on best practices, emerging health issues, and innovative research, rural providers have the additional challenges of having more clinical responsibilities because they are part of smaller practices, being geographically isolated, and practicing in Health Professional Shortage Areas.

Considerations for Policymakers

Considerations and potential solutions for policymakers working to expand access to treatment for opioid use disorder include:

Addressing regulatory barriers that affect buprenorphine access

- Expand the scope of the April 2021 HHS guidelines to further increase access to buprenorphine. In April 2021, HHS issued guidelines that certain eligible practitioners (e.g., those with a valid U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency registration and a valid state medical license for the state in which they deliver care) can treat up to 30 patients with buprenorphine without applying for a buprenorphine waiver. Reducing regulatory burden further, by permanently eliminating buprenorphine-specific training requirements and increasing patient limits, will increase access across the board. Additionally, funding available from eliminating the buprenorphine waiver could be used to support provider education in foundational training programs.

- Make flexibilities provided during the COVID-19 pandemic permanent. Policymakers could consider permanently waiving federal requirements that require people seeking opioid use treatment to complete an in-person visit to initiate buprenorphine treatment. Retaining exceptions that have permitted prescribers to initiate buprenorphine treatment via a telehealth appointment and prescribe across state lines would preserve this expanded flexibility.

- Loosen insurance-based restrictions on coverage of buprenorphine treatment. Rural providers cite financial or reimbursement concerns as a barrier to prescribing buprenorphine. Policymakers could consider rescinding prior authorization requirements and increasing provider reimbursement rates for buprenorphine prescribed to Medicaid-covered opioid abuse disorder patients.

Seizing opportunities to integrate telehealth for rural communities

- Encourage telehealth integration with local and regional infrastructure. While telehealth and recent investments in broadband access create an opportunity for expanded access to care and treatment, the increased use of telehealth may present new barriers and challenges, such as a lack of technology literacy among patients. Policymakers could consider telehealth initiatives that address the diversity of needs in service delivery, integrate with other care settings and contexts, and avoid supplanting efforts to build up local infrastructure.

Exploring innovative solutions to travel and transportation barriers for rural residents

- Local initiatives in different parts of the country, such as Project RIDE in Philadelphia, promote the use of mobile vans to initiate buprenorphine treatment and provide treatment until patients enter a treatment program. This solution could be used to address transportation issues that rural patients face. A recent Drug Enforcement Administration ruling, which allows DEA-registered opioid treatment providers to establish and operate mobile methadone vans without obtaining a separate DEA registration for each mobile component, increases access to this type of treatment. At the same time, state regulations may limit the impact of this new ruling.

Strengthening the rural health care workforce

- Federal and local policymakers and foundations could consider directing funding to provide behavioral health content to medical students during their foundational training. In addition, telementoring models such Project ECHO could help rural providers acquire the expertise they need to treat opioid use disorder and stay up to date on best practices.

Listening to people in rural communities

- State and local treatment authorities should expand opioid abuse disorder services in consultation with people in rural communities. Federal and local funders should build in time and resources to allow for community engagement and addressing the social determinants of health.

Conclusion

Rural areas, compared to their urban counterparts, have substantially lower access to treatment for opioid use disorder despite being similarly affected by the opioid crisis. Our analysis provides a better understanding of how county-level need for OUD treatment intersects with lack of access, with a goal of providing policymakers with evidence so they can better target and prioritize resources to address low buprenorphine prescribing capacity.