Promising Strategies to Prepare New Teachers in a COVID-19 World

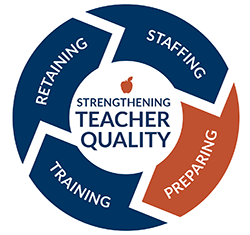

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly disrupted our education system, changing what classrooms and learning look like on a day-to-day basis. Educators are navigating a constantly shifting landscape, with the health of students, teachers, and the community at large at stake. In this series, AIR experts provide their insight into evidence-based practices and approaches for facilitating high-quality instruction—from attracting, preparing, and retaining teachers to providing them with professional learning opportunities—even during uncertain times.

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly disrupted our education system, changing what classrooms and learning look like on a day-to-day basis. Educators are navigating a constantly shifting landscape, with the health of students, teachers, and the community at large at stake. In this series, AIR experts provide their insight into evidence-based practices and approaches for facilitating high-quality instruction—from attracting, preparing, and retaining teachers to providing them with professional learning opportunities—even during uncertain times.

Teacher preparation is designed to train future teachers for the classroom. High-quality preparation programs provide candidates with the opportunity to apply what they have learned, to gain hands-on experience in real classrooms, and to work directly with diverse learners in a supervised context. While research on teacher preparation is limited, there is a positive connection between teachers’ preparation in their subject matter and their performance. For example, fully prepared special education teachers are not only more likely to remain in the profession; they’re also improving outcomes for students with disabilities.

With the uncertainty around the 2020-2021 school year, it is perhaps even more important to ensure that new teachers are prepared to take on the challenges that await them. Lynn Holdheide, managing technical assistance consultant at AIR and senior advisor and former director for the Center on Great Teachers and Leaders, explains how preparation programs are responding to the coronavirus pandemic and shares some innovative ways that school districts and programs are preparing teachers.

Q: How has the pandemic affected teacher preparation programs?

Traditional programs are generally offered through a college of education as four-year undergraduate degrees. Those curricula typically combine subject matter instruction, pedagogy classes, and field experience. Teachers in training typically go through a period of student teaching, which is generally unpaid, and are often required to take a battery of assessments before they receive their degrees.

Under the Every Student Succeeds Act, states can use Title II A funds to establish alternative preparation pathways, such as teacher and leader academies. Partnerships or individual organizations, including state education agencies, districts, institutes of higher education, regional service agencies, and professional organizations, can organize and support teacher residency programs.

Holdheide: Enrollment in educator preparation programs has already been on a decline, and while economic uncertainties have prompted people to switch careers and become teachers in the past, potential candidates may not have the time and money to become certified in the current economy.

Teachers develop competencies through continued practice. Top preparation programs allow teacher candidates to apply their learning in real classrooms with real students. Even if schools reopen, which is not certain, districts may not want candidates on site, as they try to limit additional COVID-19 exposure to staff and students. Before the pandemic, it was difficult for future teachers to secure high-quality clinical placements. Some of the offerings— microteaching, case-based instruction, video analysis, virtual simulations and lab-like experiences—that preparation programs developed in response to that could help prepare teachers now. (This brief from Center on Great Teachers and Leaders and the CEEDAR Center explains how these opportunities work.)

It may also be necessary to explore quicker pathways into the profession—without compromising quality—to ensure a sufficient pipeline of teachers. For example, programs should focus on a core set of skills, particularly high-leverage practices, that can be learned and implemented by novice teachers. Additionally, candidates should have early and continual experiences with students, either in classrooms or through virtual simulation software programs. Likewise, we should explore programs that offer financial incentives to future teachers, such as payment for field placements, student teaching, and/or residency programs.

Q: What are some ways that teacher preparation programs have adjusted to this new environment?

Holdheide: States and programs have responded differently, but there are some commonalities in their approaches. Here are three.

- Certification and Licensure. States are either using existing emergency waivers or creating new waivers to certify teacher candidates who are unable to complete program requirements due to the pandemic.

- Clinical/Field Experience Requirements. In many cases, school closures have prevented teacher candidates from fulfilling the program’s clinical requirements. Some states have waived the clinical requirements altogether; some are using conditional waivers, relying on programs to validate candidate competency and readiness; and some have maintained existing requirements.

- Assessments. Since testing facilities were closed, states have either waived the assessment requirement altogether, allowed candidates additional time to complete the assessment, or maintained assessment requirements.

The American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education (AACTE)’s Policy Map and Deans for Impact Policy Database show these decisions across states.

While these approaches are necessary in today’s context, that doesn’t mean we can relax our teacher quality standards. Teachers are already leaving the field at high rates. Without sufficient preparation, new teachers will flounder and likely leave the profession.

Q: How can these programs prepare teachers for distance learning?

Holdheide: The rush to distance learning with little to no training for teachers is troubling, and teacher preparation programs should learn from this experience. Research shows that effective distance learning requires thoughtful design decisions to ensure that historically marginalized students have equitable access to instruction and opportunity to achieve.

Instead of offering separate courses on distance learning, teacher preparation programs should strengthen existing coursework and field experiences to prepare teachers to use technology effectively in virtual or blended learning environments. This way, teachers will adopt strategies to enhance student learning in any context.

Q: What else should educator preparation programs do to support teachers in uncertain times like these?

Holdheide: Preparation programs should focus on two areas—both of which require partnership from the state education agencies and districts.

First, preparation programs should leverage the Every Student Succeeds Act or the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act funding to create effective and expedient alternative pathways for career changers to enter the profession. States and districts may cut teaching positions to alleviate their budgetary shortfalls, but they’ll still have to address existing teacher shortages, especially those in hard-to-staff subjects and schools.

Second, novice and veteran teachers will both need support adapting to this new reality. Preparation programs can support teachers through high-quality mentoring and induction programs. They can also recommend teacher candidates to schools as viable options to support additional student needs during this time.

Q: What role should schools and districts play in teacher prep?

Holdheide: States, districts, and educator preparation programs all have a stake in attracting, preparing, and supporting teachers. Even in “normal” times, partnerships between districts and educator preparation programs are critical, but that is especially true now. A two-way partnership allows educator preparation programs to respond to district needs, while the districts provide the programs with virtual or blended learning environments for candidates to hone their skills.

CEEDAR, the GTL Center, and AACTE recently released a guide that explains how districts and programs can leverage teacher candidates while they accrue hours toward their clinical practice time. This might include having the candidates provide individualized support to students with asynchronous learning, support assignment completion, ensure materials are accessible, or reinforce skills development to student groups in breakout rooms. This could be a win-win situation, as potential learning loss will likely require “all hands on deck” to meet all student needs.